By Mayu Kanamori (artist, born in Tokyo and based in Sydney)

If I answer that terribly limiting question, Where do you come from? I was born in Tokyo, but I live in Sydney now, another question usually follows: But where is your home? This second question assumes that there can only be one home, and that our identities are defined by affiliation to one sacred location. My home is where my loved ones are, and so my home exists in more than one place, I answer.

Before the governments’ pandemic measures closed national borders, I was fortunate to be able to travel back and forth between Japan, where my mother, sisters, and extended family live, and Sydney, where my partner and friends live. Even allowing for travel time to and from the airport, and the long check-in for international travel, I was able to travel between these two homes in less than 14 hours. Today, including quarantine periods at both ends, travel between homes could take longer than the time it took in the days of steamships, when the Immigration Restriction Act was in force, and exemptions for passage across borders, harder to come by.

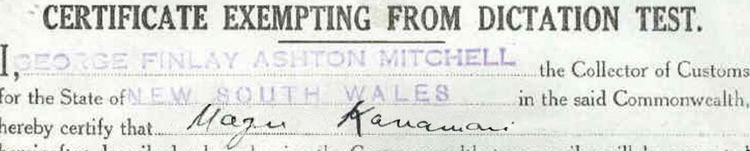

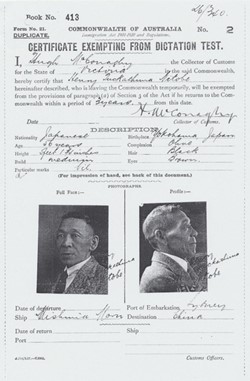

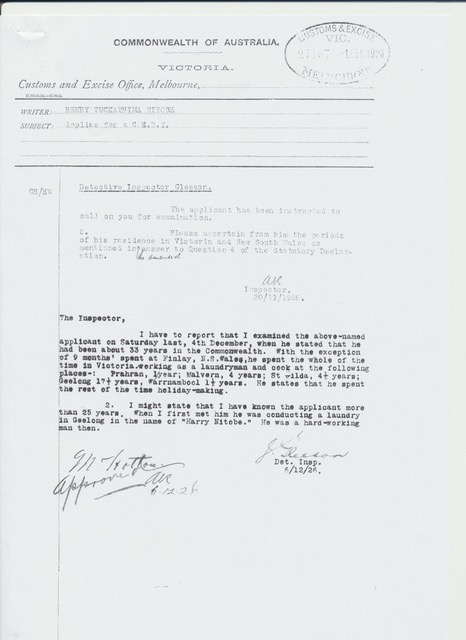

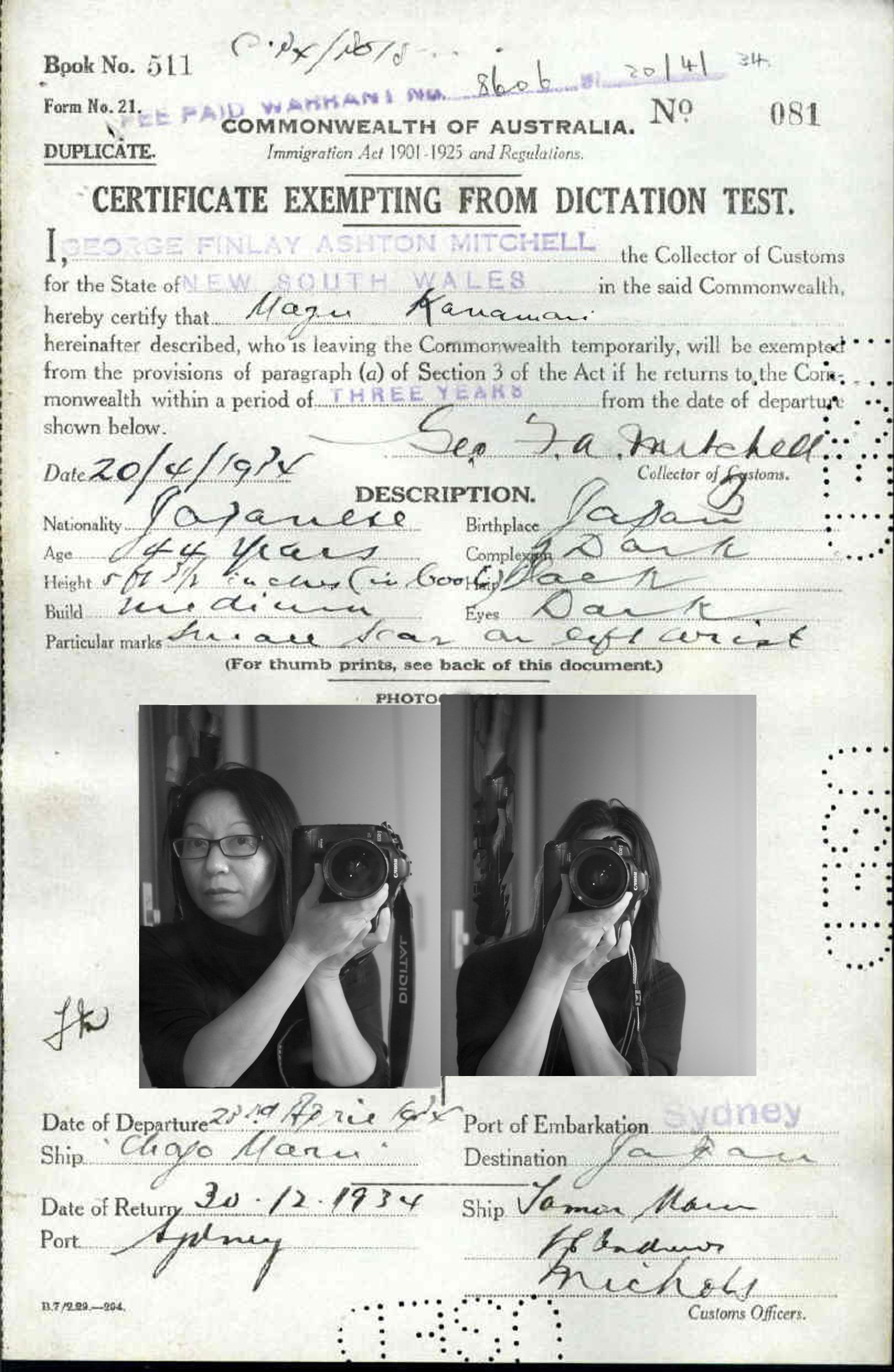

As an artist working with themes related to Japanese experiences in Australia, I have often searched the National Archives for copies of the Certificate Exempting from Dictation Test (CEDTs) to give me some insight into the life stories of our pioneering predecessors. At times these records were all I had to find out what may have happened to these people. In the case of Japanese migrants, if they had remained in Australia until the 1940s, there are also Internee Service and Casualty Forms and dossiers created by government departments before and during the war. Unlike most other documents, however, the CEDT offers a visceral understanding of a life once lived; for instance they are the only records that include photographs. A sense of connection may be felt through their subject’s timeless gaze, looking straight at the camera, which makes me feel that they are looking straight at me. Sometimes I would print the document and place my hands on their handprints.

Some people have multiple CEDTs on record, their photographs showing how they matured over the passing years, and at the same time, informing me that they periodically returned to their other homes, just as I had been doing prior to the pandemic. I see their mug shots, their head and shoulders, taken as if they had committed a crime, and find them looking very like my own series of passport photos over the last forty years.

Photographs, before they became pixel images on a screen, were thought as a proof of the existence of the subject. These people lived, and were photographed, perhaps with the sense of purpose and excitement which comes from making travel preparations; perhaps with a sense of resignation, much in the same way we intuit a lack of agency when we queue at the post office to have our passport photos taken; or perhaps even a sense of pride in simultaneously belonging and not-belonging to one place.

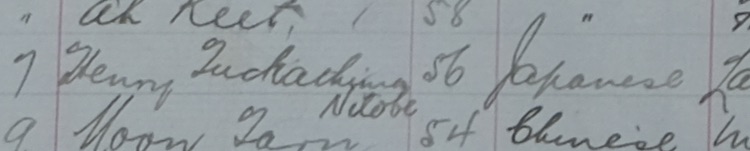

As much as the Immigration Restriction Act is criticised today, the resulting CEDTs gave passage to those who wanted to return to loved ones, both in Australia and elsewhere. Today, for artists like myself, and more especially for descendant families, the CEDTs give us a strong emotional connection to our Elders past. I am grateful to have been able to contribute in a small way to the Victorian CEDT Index, and to bring to light the records of the eight Japanese men I found, and the lives they lived and the people they loved.

Mayu Kanamori

Mayu Kanamori is an artist, born in Tokyo, and based in Sydney. Her works include Through A Distant Lens, a play based on the search of lost photographs taken by a Japanese Australian photographer Yasukichi Murakami (1880-1944) and You’ve Mistaken Me For A Butterfly, a performed poetry and film about a Japanese woman involved in an assault case in Western Australia during the goldrush. Mayu is a founding member of Nikkei Australia, a group which promotes research, study, arts, cultural practices and community information exchange about the Nikkei (Japanese) diaspora in Australia. She was a contributor to Nikkei Australia’s Cowra Voices and the Cowra Japanese Cemetery Online Database. Mayu helped CAFHOV check the Japanese names in the Victorian CEDT Index.